From the marbled Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library to the Saarinen-designed Ingalls Rink known affectionately as “The Whale”, explore highlights of Yale’s stunning architecture.

Browse Gallery

Lawrance Hall, 1885-86

Architect: Russell Sturgis, Jr. (1836-1909, M.A., Honorary, 1872)

Between 1869 and 1876, Russell Sturgis completed the troika of Durfee Hall, Battell Chapel, and Farnam Hall at the corner of College and Elm Streets. It was fitting, then, that Sturgis was again tapped for Lawrance Hall, completed in 1886 and adjacent to Farnam on College Street. The layout of Lawrance is almost indistinguishable from those of Durfee and Farnam, with their brick façades evoking the red-hued Old Brick Row buildings that they replaced. It is, however, the towers and turrets of Lawrance’s College Street front that are most memorable.

Connecticut Hall, Old Brick Row, 1750-1752

Architect: President Thomas Clap (1703-1767)

The only surviving building from the Old Brick Row, Connecticut Hall is the oldest building on Yale’s campus. Despite its name and long history, however, Connecticut Hall is in many ways a Harvard building — its design is rooted in that of the 1720 Massachusetts Hall in Cambridge. Regardless, the dormitory that Clap built provided much-needed housing for Yale, and its construction marked the beginning of the entryway system at Yale. Ultimately transformed from a dormitory into a meeting hall and office space, Connecticut Hall was given a neighbor in 1925, McClellan Hall, which is so architecturally dependent on its twin that students have been known to cry out, “For God, for Country and for Symmetry.”

Dwight Hall (Old Library), 1842-46

Architect: Henry Austin (1804-1891)

Henry Austin, who designed Dwight Hall, built more for the City of New Haven than for Yale itself — his work for the Elm City includes its City Hall and the widely acclaimed gates of the Grove Street Cemetery. But his time in New Haven began at Yale, where he designed a brownstone-clad library that was converted into Dwight Hall in 1930. Austin’s was the first building on campus designed in the Gothic Revival tradition, marking a significant departure from the Old Brick Row of the 18th century, and thereby setting the principal direction of campus architecture to this day.

Branford and Saybrook Colleges (Memorial Quadrangle), 1921

Architect: James Gamble Rogers (1867-1947, B.A. 1889, M.A., Honorary, 1921) Gate by Samuel Yellin (1885-1940)

The list of buildings James Gamble Rogers designed for Yale between World War I and World War II is almost endless; it is certainly too long to include here. But none is finer than the Memorial Quadrangle, today housing students in Branford and Saybrook Colleges in a Gothic residential complex with six variously proportioned courts that provide a sense of intimacy and grandeur in the shadows of the 216-foot-tall Harkness Tower and behind Samuel Yellin’s masterful iron gate.

Street Hall, 1864

Architect: Peter B. Wight (1838-1925)

When first completed, Street Hall stood alone on the corner of Chapel and High Streets, a beacon of Yale’s then-nascent engagement with New Haven that could, per a donor’s wish, be entered either from the Old Campus or from the city sidewalk. When an upcoming renovation of the building is complete, though, visitors will be able to enter it from yet another side — the Yale University Art Gallery across High Street. The Art Gallery will expand across the bridge over High Street into Street Hall, filling the space left open after the History of Art Department moved to the Loria Center in 2008. The exterior of Street Hall will remain the same, though, with its restless, asymmetrical massing and its mix of dark and light stones.

Yale Center for British Art, 1977

Architect: Louis I. Kahn (1901-1974, faculty 1947-59, D.F.A. 1965)

Chapel Street between High and York Streets yields the pleasure of seeing Louis Kahn’s work at the beginning of his career, with the Art Gallery extension he designed in 1953 on the campus-side of Chapel and, across from it, the Yale Center for British Art completed in 1977, three years after the architect’s death. Kahn’s engagement with light is obvious in both museums, as is his engagement with the street. Amazingly, the actual entrance to the Center for British Art at the corner of High Street is rather difficult to find below the concrete framed-stainless steel façade; visitors can seem bewildered until they see, some 40 feet behind the low recess, a pair of glass doors leading to top-lit atrium, one of two in the building. Upon entering the Center for British Art, then, visitors discover the true magic of Kahn’s work — the way in which light and visitor and art interact.

Old Art Gallery, 1928

Architect: Egerton Swartwout (1870-1943, B.A. 1891)

It is difficult to imagine Chapel Street today as Egertown Swartwout did in 1926. Swartwout’s proposal for an Art Gallery to unite the University’s then-scattered art holdings was to extend all the way along the length of Chapel Street from High Street to York Street. The design was not fully realized because of limited funding; Swartwout had planned for seventeen Italian Gothic arches, but only five were built. The architect’s impact was still great, as the bridge connecting the building to Street Hall above High Street reframes the boundary between city and campus as no other Yale building does. Following the 2006 renovation of Louis Kahn’s addition, the Swartwout portion is also scheduled to be renovated.

Rudolph Hall (Art & Architecture Building), 1963

Paul Rudolph (1918-1997, Dept. of Architecture chairman 1958-65)

Restoration by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects

Charles Gwathmey (b. 1938, M.ARCH 1962)

Paul Rudolph’s Art & Architecture Building is called Brutalist with good reason, especially by those students and teachers who brush against its rough, corduroy-like walls. But it is also an intensely lyrical building that fittingly completes the march of art buildings on Chapel Street. Its vast, open spaces scattered among 37 levels on nine floors were intended to encourage interaction among students of art and architecture who might otherwise remain cloistered from one other. With the completion in 2000 of Holcombe T. Green Hall to house the School of Art, Rudolph Hall is the exclusive home of the School of Architecture. Rudolph Hall has had a difficult past: It suffered an unexplained fire 1969, and was not treated well for much of its subsequent history until the just-completed renovation by Charles Gwathmey that has restored the building to glory.

Loria Center for the History of Art, 2008

Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects

Charles Gwathmey (b. 1938, M.ARCH 1962)

There are few tasks in the world of architecture as daunting as the one Charles Gwathmey faced in designing the Loria Center for the History of Art: To build a neighbor for Paul Rudolph’s Art & Architecture Building, and make it one that is both an appropriate addition and a distinctive design in its own right. The 87,000-square-foot building is a little of each — the use of zinc and limestone to clad its main volume establishes an identity for the History of Art building, while acknowledging the palette of materials used not only in Rudolph Hall but also those of James Gamble Rogers’ residential colleges just down York Street and Louis Kahn’s two museums on Chapel Street. Gwathmey’s design is at its best, however, on the inside, where long hallways terminate in spontaneous views of the campus that unite the Loria Center not only with Rudolph Hall but also with much of Yale and New Haven.

Davenport College, 1933

Architect: James Gamble Rogers (1867-1947, B.A. 1889, M.A., Honorary, 1921)

Davenport College sits on a location that called on James Gamble Rogers both to protect the aesthetic he established with the Memorial Quadrangle and to establish a new and distinct design across York Street. Indeed, while Davenport’s Gothic front seems almost entirely in unison with the fine stonework of the Memorial Quadrangle, the College seems far different once inside its gates. Here, the Georgian style takes over and one is reminded not of Branford or Saybrook College, but rather of the red brick of Yale’s 18th century past.

Morse and Ezra Stiles Colleges, 1962

Architect: Eero Saarinen (1910-1961, B.F.A. 1934, M.A., Honorary, 1949)

Eero Saarinen remarked during the construction of Stiles and Morse Colleges that he had embarked “on unchartered waters” in his design. In many ways, this is true: The coarse walls of a poured concrete-and-stone mixture with thin strips of vertical windows and the complex’s overall massing and layout (there are no right angles) are indeed unique. What is most splendid about Stiles and Morse, however, is that despite their idiosyncratic modernity they are nonetheless in harmony with the rest of campus, with two towers that establish strong ties to the nearby Payne Whitney Gymnasium and Hall of Graduate Studies, and a winding alley between the two colleges that at once calls to mind the streets of Italian hill towns such as San Gimignano and the intimate courtyards of James Gamble Rogers’s residential colleges of the 1920s.

Payne Whitney Gymnasium, 1932

Architect: John Russell Pope (1874 – 1937, M.A., Honorary, 1924)

John Russell Pope had bold plans for Yale — his 1919 master plan called for a consistent Gothic aesthetic on campus and the creation of axes and vistas to unify what was at the time a haphazard collection of buildings. Although his vision was never realized in full, the Cross Campus of today is essentially Pope’s brainchild; interestingly, had Pope had his way, the Cross Campus would have been home to a large gymnasium. Instead, under the watch of James Gamble Rogers, the Payne Whitney Gymnasium was placed at the edge of the Central Campus, although the commission went to Pope. His building, jokingly referred to as the “Cathedral of Sweat,” is almost spiritually Gothic, and its 240-foot-tall tower rising from a broad base is certainly large enough to house all the athletic activities one could imagine.

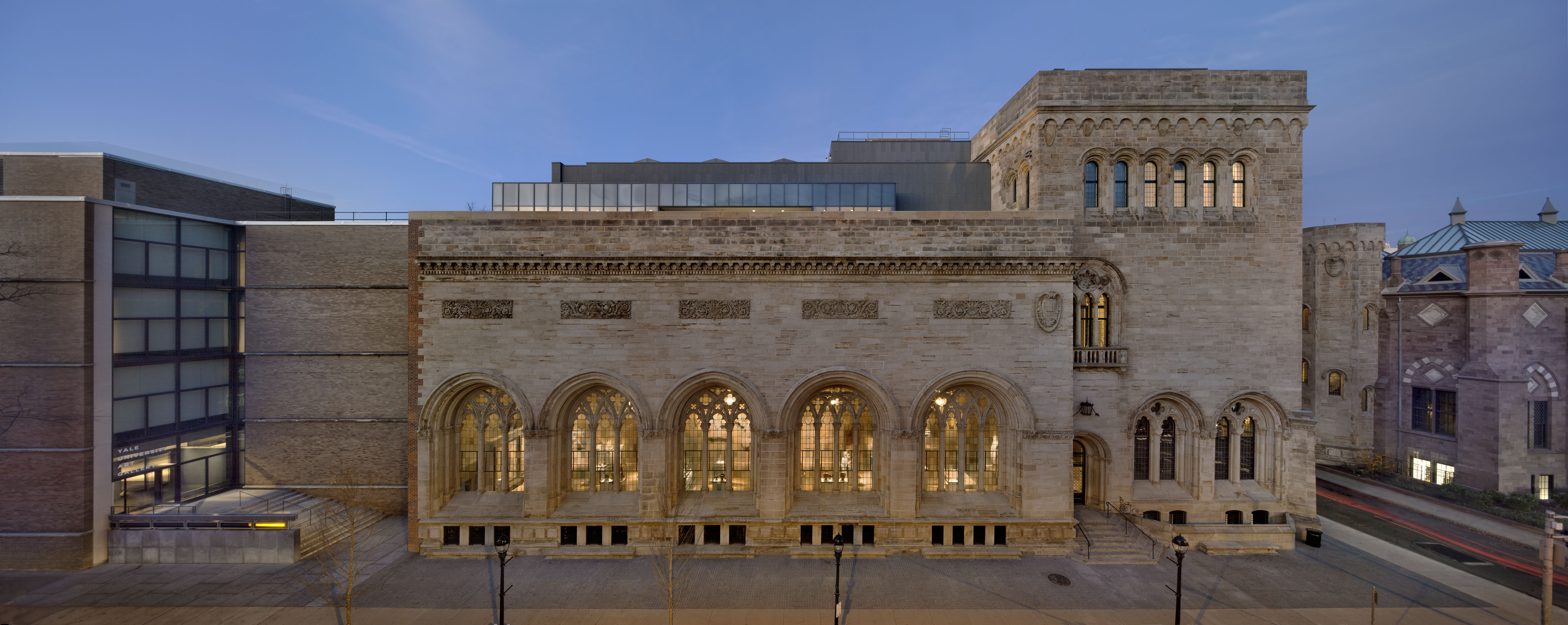

Sterling Memorial Library, 1930

Architect: James Gamble Rogers (1867-1947, B.A. 1889, M.A., Honorary, 1921)

Located at the heart of today’s Central Campus, the Sterling Memorial Library is Yale’s most prominent — and perhaps grandest — building. Ostensibly designed by James Gamble Rogers, the Library owes its fundamental character to Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, who was the architect of record for the project until his death in 1924. It was Goodhue who devised the concept of a low, intensely Gothic building with a stack tower at the back. Rogers developed Goodhue’s design but reconfigured its plan to provide for a nave-like space leading to the reference desks. Various special reading rooms are arranged to either side, including the Starr Main Reference Room and the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library, added in 1998. In the final realization it is Gamble Rogers’s hand clearly at work, revealing in the building’s details his superb wit. Indeed, as a carving on the Library’s Wall Street façade exhorts in Latin, Sterling is a place to “make haste slowly.”

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, 1963

Skidmore, Owings and Merrill

Gordon Bunshaft (1909-1990)

Sculpture Garden by Isamu Noguchi (1904 – 1988)

The Beinecke is a building that has grown on Yale. At first decried by many as bombastic, it now has a strangely quiet presence in the midst of the vast granite-paved expanse of its plaza, punctuated by a sunken courtyard with sculpture by Isamu Noguchi. Inside, there is no doubt that this is a building that whispers. The Vermont-marble panels filter sunlight so that the Beinecke is dim at all hours; its books are housed in a six-story glass box around which a second-floor hall exhibits treasures from the collection. Hidden from view is the expansive space below ground that provides space for research and study. In its abstraction, the Beinecke stands in contrast to its neighbors: Howells & Stokes’s Woodbridge Hall, and the robustly classical 1901 Bicentennial Buildings — Woolsey Hall and Commons — designed by Carrere & Hastings.

Malone Engineering Center, 2005

Cesar Pelli & Associates

Cesar Pelli (1926 - , D.F.A., Honorary, 2008)

Gazing north from the fourth floor of Cesar Pelli’s Malone Center, the view is seemingly endless. Four stories provide all the height one needs in New Haven: The sights range from East Rock to West Rock, from Ingalls Rink to the Kline Biology Tower, from the Yale of today to the Yale of tomorrow. The design is both sustainable (it earned LEED-gold certification) and social, encouraging interaction among scientists. The Malone Center’s combination of a boldly curved glass façade along its Farmington Canal front and a stone façade along Prospect Street recalls the whimsically two-sided Davenport College.

Ingalls Rink, 1958

Eero Saarinen (1910 — 1961, B. Arch, 1934; M.A., Honorary, 1949)

Renovation and expansion by Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates

Kevin Roche (1922 — , D.F.A., Honorary, 1995)

Whether you think it looks like a Viking ship, a turtle, or a whale, the Ingalls Rink is without a doubt one of Yale’s most important examples of post-war modernist architecture. While the average hockey rink is more of a shed than anything else, this rink’s swooping roof seems to echo the movement of skaters, while providing seats for 3,000 spectators in a remarkably intimate setting. Of course, Ingalls is an oddly located building, and does not make much of an attempt to fit in with its residential and academic neighbors. A comprehensive renovation, set for completion in 2010 and overseen by Saarinen’s former deputy, Kevin Roche, promises to restore Ingalls to its original splendor and accommodate new programmatic needs.

Kline Biology Tower, 1965

Philip Johnson Associates

Philip Johnson (1906-2005, D.F.A., Honorary, 1978)

The Kline Biology Tower, Yale’s tallest building, sits at the top of Science Hill. At 14 stories, the tower may be too tall, but Johnson’s design is masterful in its aesthetic connection with buildings centuries older on campus. Indeed, the handling of the brick and brownstone of Kline ties it — in color and, to some extent, in shape — to Sturgis’s work on the Old Campus and other surrounding structures. Johnson was also responsible for the Kline Geology Building and the extension to the Chemistry Building, weaving these together with earlier buildings to define one of Yale’s most masterful courtyards.

Sterling Divinity Quadrangle, 1932, 2003

Delano & Aldrich

William Adams Delano (1874 – 1960, B.A. 1899, M.A., Honorary, 1939)

Restoration and renovation by Kliment & Halsband Robert Kliment (b. 1933, B.A. 1954, M.ARCH, 1959)

The Sterling Divinity Quadrangle, sitting at the extreme northern end of Yale’s campus and commanding a high site on Prospect Street, is Delano and Aldrich’s interpretation of Jefferson’s University of Virginia Campus, employing a red-brick Georgian style for buildings around a large lawn. At the head of the lawn and the site’s highest point, where Jefferson had located a library, sits the Marquand Chapel. Threatened with demolition in the 1990s, the quadrangle was renovated in 2003.

Yale Psychiatric Institute, 1989

Frank O. Gehry (b. 1929, D.F.A., Honorary, 2000)

Note: There is no public access to this building.

The Yale Psychiatric Institute, Frank Gehry’s only design at Yale, was realized on a very tight budget and awkward site. The complex, now known as the Yale-New Haven Psychiatric Hospital, gives off the impression of a village of small buildings grouped around a courtyard. While the Institute’s windows are square and plain, the buildings themselves are a study in geometry and materiality. A copper arc tops the complex, covering a gym; brick and stucco finishes cover wings that jut out at irregular angles. Designed to meet the needs of 66 adolescent patients, the Institute sits at the edge of the Medical School’s campus, near to the Hill neighborhood of New Haven.

Credit to those that made this gallery possible:

Text: Paul Needham

Editor: Robert A.M. Stern

Photography: Michael Marsland

Design: Nicholas Appleby

Special thanks to:

Leo Stevens, Barbara Shailor, John Jacobson, Lesley Baier.